.........................................................................................................................................................................................................

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................

palmares | a funny guy | the stolen vuelta | a peiper's tale |the spanish years |

the small yin | setting the record straight | millar on motorbikes | the book |

robert millar colnago c40 review | 1988 winning magazine interview | training | the outsider |

2008 interview | british road champion | the 2011 tour de France

Honour at last for Scotland's king of the mountains. Richard Moore.

many thanks to iain lindsay for the photo of robert's entry in the scottish sports hall of fame and to richard moore for permission to reproduce this article

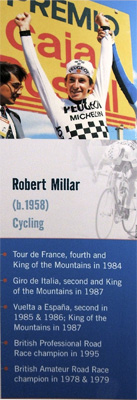

When he retired, Robert Millar disappeared without fanfare, but in a scenario that will be familiar to some Dundee footballers. It was in June 1995, and he had just won the British road race championship in crushingly dominant style, when his French team, Le Groupement, went bust. For Millar that was the end; there was no announcement, no official retirement, nothing. Deprived of a 12th crack at the Tour de France, he simply disappeared.

There has never been a better time for a reappraisal of Millar's career, and some long-overdue recognition, when he was one of 14 men and women inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, though Millar himself was, predictably, nowhere to be seen, and his whereabouts are unknown to all but a very few.

Millar, the skinny boy from the Gorbals who rose to become a giant of the Tour de France, never did try too hard to be an enigma. It came naturally to him. And it only heightened his appeal to those of us who followed the Continental cycling scene from afar. He was a beacon, an astonishing and exciting talent during a period when English-speaking cyclists - never mind Scots - were all but unheard of. Millar was simply, and very deliberately, unheard.

Following the progress of the Tour de France from Scotland was far from easy in the mid-eighties, but Millar made it worth the effort. In those days there was a weekly half-hour round-up on ITV's World of Sport, Dickie Davies introducing a snapshot of an alternative and faintly exotic world of sport, where masses of fanatical supporters spilled on to the road to acclaim heroes whose names were daubed on the tarmac in big, bold, white letters. The narrow, twisting passes of the Alps and Pyrenees thus read: Hinault, Fignon, LeMond, Millar.

The nature of the coverage only made Millar's achievements in that awesome event seem even more remarkable and otherworldly. Memories now are of grainy footage, and of this malnourished-looking young Scot, wearing a tiny stud in his ear and a mop of curly hair, dancing through the crowds, or out of the mist that clung to the snow-capped peaks of the Pyrenees, his favourite stomping ground.

It was the stuff of dreams, and at least one 11-year-old was inspired to write to Jim'll Fix It, begging for the chance to cycle with the great Robert Millar. Two years later Channel Four began to broadcast the Tour every night, possibly as a consequence of Millar's exploits in the great race.

'Millar never did try too hard to be an enigma. It came naturally to him'

Whether Millar desired a bigger audience back home is a moot point. It's unlikely he would have cared, for his disappearance from his native Glasgow proved as final as his eventual disappearance from cycling. He had elected by then to follow a cul-de-sac too narrow to attempt a u-turn, and at its end was a career as a professional cyclist. In 1979 he moved to France to join the elite ACBB, the world's top amateur team, abandoning an apprenticeship at a Glasgow pump manufacturer, where his only concern had been to lock himself in the toilet and sleep so he'd be well rested for training later.

In France Millar's dedication was frightening. Another Scottish amateur who raced there in the late seventies tells of going to visit the monosyllabic Millar in his apartment, and being taken aback by the severity of his haircut. The haircut was brutal, and so was the explanation. "It's in case I weaken and want to go to a disco," said Millar, with a look of grim determination.

It was by this that he succeeded, and after he turned pro in 1980 his progress was stunning, culminating in 1984 with fourth at the Tour, still the highest placing ever by a British rider, and, incredibly, the King of the Mountains title.

There is a postscript to Millar's career. He began writing, displaying an acerbic wit that hitherto had been enjoyed only by a few. In 1997 he became British coach, and the following year he managed the Scottish team in the Prutour, an eight-day round-Britain stage race, with a field that included Millar's successor as British No.1, Chris Boardman.

It also included me, riding for Scotland, under the management of Britain's best-ever stage race rider. None of us in the Scotland team was going to win the race, but the experience was unforgettable, not so much for the racing, but because we got to know Millar. And it gave at least one of us good reason to be relieved that Jim'll Fix It never replied, because Millar would probably have taken the piss. His sense of humour was dry, he could be irascible, and he was razor sharp. And as one rider discovered as he searched frantically for his race number in the minutes before a stage, he enjoys a practical joke.

It was all too brief. Millar disappeared again, and he is apparently in no mood to be discovered, least of all by members of the press. Rumours abound: he lives in the south of England, he's in Australia for the winter; he still writes; he's a martial arts expert and a motorbike fanatic. He probably still rides his bike, too, since at the Prutour he made time to ride for a couple of hours after every stage.

His name has faded from the passes of the Alps and Pyrenees, but it's in the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, and deservedly so. Somewhere, Millar himself might even be a little bit chuffed. But I wouldn't bet on it.

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................palmares | a funny guy | the stolen vuelta | a peiper's tale |the spanish years |

the small yin | setting the record straight | millar on motorbikes | the book |

robert millar colnago c40 review | 1988 winning magazine interview | training | the outsider |

2008 interview | british road champion | the 2011 tour de France