..........................................................................................................................................................................................................

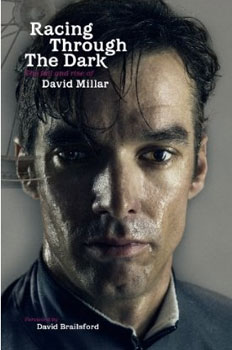

racing through the dark - david millar. orion books softback 354pp illus. £12.99

i have just finished designing and printing an a3 leaflet for one of our local primary schools, a leaflet showing, by means of the kids' drawings overlaid on photos, animals and birds that you'd find in the islay countryside and seaside. next to the name of each animal or bird is a small white circle allowing recipients of the leaflet to tick when they have spotted the wildlife in question. almost like the i-spy books of yore.

the brief was fairly laissez faire, allowing a bit of room to manoeuvre as to where items were placed on the page, though by and large, they already had it sussed how the end product was to look. however, what was specifically instructed was that the text accompanying each child's drawing (in english and gaelic) should be set in comic sans apparently because "it's easier for the children to read". that is, of course, utter hogwash. along with brush script, comic sans must be one of the most appalling typefaces known to mankind. yet for reasons best known to all four of the island's primary schools, virtually everything they commit to print has to use this font.

as someone who loves a constructive argument, i debated over the possibility of a lengthy discussion as to why i thought an alternative typeface ought to be used; but then thought better of it. in the words of lord carlos of mercian, 'the customer is always wrong'. ultimately, and particularly in cases such as this, whoever pays the graphic designer (within reason) can have what they want. i do not receive greater remuneration for educating the client as to the finer points of modern typography. so comic sans it is.

in the grand scheme of things, this is a trifling matter, for it is unlikely that unemployment would have followed from either my refusing to deal with comic sans, or even having the temerity to replace it with what i considered a more appropriate style of lettering. others, however, may not fare so well.

this, though reduced to a more superficial level, is the crux of david millar's book 'racing through the dark', subtitled 'the fall and rise of ...'. at its most bare, it is a narrative exploring and exploding the iniquities of peer pressure, something we all experience in every day life. it is the measure of an individual's character as to whether they bow to such pressure, or simply let it walk on by, though those with an unflinching stance against something so embedded in modern culture are perhaps few and far between. millar, with his privileged beginnings and teenage years seemed convinced that he would not allow any undue pressures to shape the way he went about his adopted profession.

the opening chapter of the book takes no prisoners ('scuse the pun), describing the feelings and emotions of waking up in a prison cell in biarritz. if there was ever the slightest doubt that david millar was going to plaster over the cracks and simply provide us with a manual on the art of time-trialling, this chapter is testament to the contrary.

"i am in a french prison cell, below biarritz town hall, in an empty basement. a smell of piss and disinfectant hangs in the air. a drunken man shouts relentlessly somewhere in a cell down the corridor". hardly the introduction from which dreams are made of, and a far cry from riding team gb carbon at the world's time-trial championship

millar's father was in the airforce, necessitating an almost peripatetic lifestyle for the whole family. though born in malta, his formative years were spent, quite idyllically according to millar, in north east scotland. he is nothing if not repetitive in his insistance that he considers himself to be a scot, and retains affectionate affinity for the country, despite having lived there for a mere handful of years.

"i spent a few weeks up in edinburgh, the longest time i'd spent in scotland since i'd left as a child. surprisingly, given all that had happened, it felt like home. ...i would never cease to be surprised by how every scot i met treated me as one of their own. it felt good to be scottish."

his parents eventually divorced, sister frances remaining in england with david's mother, and he opting to join his father in hong kong, who had retrained as a commercial airline pilot. by all accounts, his life in hong kong fitted neatly into the box entitled hedonistic, a state enjoyed in the company of like-minded friends. "although i was drinking and smoking a bit, i was quite evangelical about chemical drugs. i found the thought of them disgusting and fundamentally wrong." millar became, as he puts it a bike perv. during his lackadaisical school years as the privileged son of a british ex-pat living in hong kong. though the early forays in the saddle were aboard a mountain bike, two of those he rode with spent time educating him to the joys of road cycling. to use a well-worn cliche, the rest is history

i recall a conversation with my teenage son, about the perils of smoking, while sitting in euston station waiting for the sleeper to glasgow. he fully concurred with my views on the evil weed, yet only a few years later, started nipping out the back door for a sly cigarette. good old peer pressure once again. despite many a substance being on the uci's banned list, such persuasion appears to be endemic within the professional peloton, with only a few (at one time) questioning whether such preparation was truly necessary to stand atop the podium. millar, rightly or wrongly, levels much of his disillusionment at cofidis, his first professional team. not so much that they enforced a regime of doping, but that they seemed either unwilling or unable to do much about it within the team.

the constant variation in racing programme; being informed that he was to race either immediately after a long stage race or, indeed, when he was patently unwell enough to participate in any form of cycling activity, not unnaturally, began to take its toll. cycle racing is a team sport, where each rider in that team has a specifically or loosely designated job during any particular race. millar, like many a professional rider began to see his position as a professional cyclist as the job that it truly is, and less akin to the joyous obsession that is the truth for many of us. with the sponsor keen for victories, the management keen to please the sponsor, and the riders beholden to the management for their ongoing contracts, acceptance that taking epo (amongst other substances) in order to fulfil the demands of his job title.

"not once did i tell anybody about the decision i'd made. there was never any question of sharing it."

most sports have rules, and indeed so do many forms of employment. you break those rules at your own risk, exactly as david millar has admitted to doing. his realisation that he had turned his boyhood obsession into a mere job may have engendered many facets, and it is perhaps ironic that his arrest came some time after he had already decided to refrain from continuing the practice. for not only did he lose this job, he became a pariah in the eyes of many who had admired his achievements; his period of drug abuse now called into question all the results he had garnered while riding clean. and the problems did not stop there, as the french tax authorities subsequently pursued him for unpaid taxes, an amount that took him several years to repay, and meantime necessitated a move back to the uk where there was some sanctuary from the french tax demands.

millar's story could not be that of anyone else in the peloton. no other cyclist that i know of has held their hand up and said "it's a fair cop, but society is to blame.", served their sentence and returned determined to rail against the drug use that seems almost endemic in top level cycling. with the peloton being pretty much a closed shop with regard to the subject, his opposition may well be making it hard to win friends and influence people, but you have to admire the guy for trying. throughout, millar is not sparing in his praise for those who have helped him through his (self-inflicted) ordeal, keen perhaps, to point out that though he is now in the role as spokesman, he could not have achieved his return without those who gathered around him.

in particular, dave brailsford (writer of the book's foreword), who was with millar when he was arrested and who also spent several hours in police custody and questioning, is singled out for praise. considering brailsford's current position as director of both british cycling and team sky, it would surely have been a comfier ride for him to have kept well clear. additionally, millar's lifetime olympic ban is not recognised by scotland when related to competing in the commonwealth games in india last year. a gold medal in the time-trial was surely ample repayment for this morsel of faith.

"i (hadn't seen) any benefits taking time out from my pro-racing schedule to race for scotland. i regretted that, and was thankful to have the opportunity to rectify it"

of course, if i were to be cynical, he would say that, wouldn't he? it's one thing to acknowledge with disdain minor events such as the commonwealth games when you're flying high in the tours and classics, but altogether another when the options are a tad more restricted and you need to curry favour (no pun intended).

though millar has come clean in a manner that i found unexpectedly frank - there are few warts hidden from view midst the 26 chapters - he has in all honesty, continued to respect the omerta of the peloton. throughout 'racing through the dark' he euphemistically refers to the team-mate who eventually made it possible for him to dope as l'equipier. the rider remains anonymous via this alias, to the end. i think it likely that anyone who knew the inner workings of the cofidis team of the era could likely figure out to whom he was referring, but this bestowed anonymity sits ill at ease with millar's born again crusade. surely to live up to his new self-appointed credentials, he should stand up and be counted, naming names?

for those of us not directly involved, it's an easy call to make. in this case, we want our cake and we'd also like to eat it please. for despite our despising of drug use in the peloton, we seem happy to endorse it elsewhere. was it not sergeant pepper's lonely hearts club band that was lauded as possibly one of the finest albums of all time? yet 'lucy in the sky with diamonds' was most certainly not referring the transportation of jewellery by aircraft.

we're a hypocitical bunch when it comes to our entertainment.

despite arguing over what it says and does not say, and who it may have exposed from the rabble, 'racing through the dark' is a well written, well paced and addictive (appropriate n'est pas?) book. none of its 354 pages can be considered padding and though there will probably always be murky goings on in top level cycle racing when so much is at stake, david millar is to be congratulated not only on 'fessing up, and recounting every last humiliation in print, but for giving us mere mortals an inkling into the machinations of the modern peloton, both good and bad.

it would also be totally remiss of me to ignore the considerable contribution from jeremy whittle who, i believe, kept david millar's narrative to manageable proportions. he has fully understood the true meaning behind the word editor

posted friday 24 june 2011

..........................................................................................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................................................................................................