.........................................................................................................................................................................................................

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................

palmares | a funny guy | a peiper's tale |the spanish years |

honour| the small yin | setting the record straight | millar on motorbikes | the book |

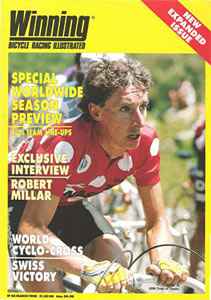

robert millar colnago c40 review | 1988 winning magazine interview | training | the outsider |

2008 interview | british road champion | the 2011 tour de France

reprinted by kind permission of Cycle Sport Magazine

In 1985, Robert Millar came the closest a Briton has to winning a major tour, but Spanish desire for a home win scuppered the hopes of the foreigner with the earring. We investigate what was possibly one of cycling's biggest ever combines. Millar provides his own commentary.

I recent years Robert Millar has said he liked the Vuelta, but at the end of stage 17 of the 1985 edition of the race he swore he would never return to Spain. Clearly wounds have healed over the years but the 'Tour of Spain that was stolen from Millar' is a story that refuses to go away.

("I never said that at all, though somebody thought it would look more spectacular if that was in their story. The words never came out of my mouth or even entered my head. I would have been crazy to deny myself the chance of winning a major race like the Vuelta.")

Jose Recio, who formed half of the 'working alliance' that gave the Kelme rider the stage and Pedro Delgado the race on those fateful 200 kilometres that separated Alcala de Henares and the DYC distillery, admitted that it was 'one of the wierdest things that ever happened during my cycling career: seeing somebody who was more than six minutes behind on general classification'.

Weird seems a polite way of describing it. Delgado's major wins – the Vuelta in 1985 and 1989 and the Tour de France in 1988 – have always been somewhat controversial, as indeed have his major defeats. In the 1988 Tour he he tested positive for probenecid, a known masking agent for anabolic steroids that was banned by the International Olympic Committee but not by cycling's governing body, the UCI. In the Vuelta 1989 Delgado was filmed by a Colombian camera crew passing an envelope to the Russian Sergei Ivanov at the start of a stage. The Spaniard later claimed it contained his address.

As for the Vuelta 1985, read on...

First the facts everybody agrees on: after a certain Miguel Indurain had become the youngest ever leader of the race on stage two, Pedro Delgado, riding for the Seat-Orbea team, took the jersey off him thanks to a fine ride to the legendary Covadonga summit. However, to quote Delgado, "I cracked the following day, my legs blocked" and on the following day's mountainous stage he lost the led to team-mate Pello Ruiz Cabestany, a gutsy rider, fond of the Classics, but no great climber.

When the Pyrenees loomed into view three days later Millar took over as leader. His initially slender lead was strengthened by a great performance in the mountai time trial form Andorra to Pal - in spite of a puncture he finished ten seconds behind time trial winner Rodriguez - ("Actually I had two bike changes. The forst one was planned to change to a heavier bike fitted with a rear disc wheel for the descent and flat run in to the finish at the top of the only climb, but the experimental Michelin punctured after only a kilometre so I had to change back to the light bike again. I had the best time up to then") and everybody thought he had only double stage winner Francisco Rodriguez and Cabestany to worry about when the race reached the mountains around Madrid.

Rodriguez was ten seconds down on the Scot, while the Basque Cabestany was just over a minute adrift. Delgado, meanwhile, had fallen away to 6-13 behind Millar.

Consequently, while three riders – Cabestany, the Colombian Rodriguez and Millar – were all in with a good chance of topping the podium in Salamanca with just two days of racing left. Only an extraordinary series of circumstances and lucky breaks could surely permit Delgado to win? But win he did.

The 200 kilometre penultimate stage included the major climbs of the Morcuera, Cotos – going up to theNavacerrada pass – and Leones, and they were then followed by 60 kilometres of rugged terrain to the finish.

Recio broke away on the flat before the Cotos climb and on the descent from Navacerrada Delgado got across to him and the pair managed – somehow – to build up a lead of seven minutes in 60 kilometres. ("I was never told who was in the front by Berland or anyone else. I only found out after the finish. I never knew what the gap was or who it was to.") By the time Millar was informed by his directeur sportif that he was on the point of losing the Vuelta; the warning had come too late.

Just 40 kilometres before, on the summit of Los Leones, Ruiz Cabestany had leaned across to the Scot and shaken hands with him, congratualting him on what seemed now to be his certain win after the Bsque and Rodriguez had failed to shake Millar off on the last of the major climbs, nobody could surely prevent Millar from taking his first major tour win. Unfortunately, nobody would prevent him from losing it either.

At this point versions of what happened start to vary very radically. The basic question concerns time references. When breaks go away the race leader and peloton rely on precise information on time gaps being relayed to them. Ramon Mendiburu, the technical director and offical timekeeper of the Vuelta, states that he was in the first car following Millar, Rodriguez and Cabestany and that time chacks were given "every two to three kilometres of the time between Delgado and the race leader. I knew that the the Vuelta was up for grabs that day. How could I not remember that?"

However, journalist Jeff Van Looy, covering the race for for the Spanish newspaper Meta 2 Mil, disagrees: "In those days you would follow the stage for the last ten kilometres and I can remember the time chacks were irregular. How could they not be, given that the race had split up completely over the last climb? There were little groups of riders in twos and threes all over the place. And they didn't let the cars through to talk". Millar's directeur sportif at Peugeot that year, Roland Berland, repeatedly claimed that he was not given ufficient information by Radio Vuelta ("Berland said he never understood what was coming over on Radio Vuelta as it was in Spanish and garbled.") and consequently would not have had the chance to react even if he had been let through.

Most importantly, Millar says that he was not given any time checks at all until there were around 20 kilometres of the stage left. All of this contrasts sharply with the chacks given to Delgado and Recio, who received at least enough information to encourage them to continue driving as hard as they could, and with the fact that Ruiz Cabestany said he knew all the time that Millar as going to lose the Vuelta, but he had to keep his mouth shut.

Then there is the question of what happened to Millar's team: none of his team-mates ever arrived to help out their leader. According to the Scot, they told him afterwards that they had been caught out by a level crossing which had stopped them for several minutes, 'only the train never came'. He refutes claims made other riders that the Peugeot domestiques overtook him after the Leones pass and formed a group ahead of him. ("Beralnd wanted to win the team prize as well so he made the guys in the team do the time trial flat out, but they all got blasted on the first col the fatal day. Only Pascal Simon was left with me when I punctured at the bottom of the second climb. As the Spaniards had attacked Simon had to be sacrificed just to get me back to the bunch, from there I had to ride acriss to Rodriguez and Cabestany who were in front of them. I caught them just before the descent started which I had to otherwise I would have been history because I didn't know the downhill at all. It was hailing at the top of the col so you couldn't see so far. Kelly and co. attacked after the third col, at the bottom of the descent, but I had no reason to chase him and I had to let him go. I couldn't chase every attack as I was alone then in a group of about 20 riders.

Kelly said later that even with four or five team-mates riding flat ot they still lost two minutes on Delgado and Recio in 20 kilometres and they'd been out there all day. The Peugeot guys said they got stopped at a level crossing when they were just behind my group and stood there for a couple of minutes before the barrier went up again. They said no train ever came.")

What is certain is Sean Kelly and his Skil team-mates were in the first chasing group, but were unable to bring back the deficit. In addition, Millar's team-mates had been burned out bringing him back to the peloton after the Scot had punctured on the Cotos climb and they were, according to Millar 'all knackered because Berland had made everybody go flat out the day before in the time-trial to try to win the tem prize as well'.

Off-the-record comments have been made suggesting that certain members of the Peugeot team may well havae been unwilling to see a British rider win in a French led squad. Whether this was true or not, Millar was left on his own to drive as hard as he could with Rodriguez and Pello Cabestany waiting for a sign of weakness.Even though he was joined by a large number of riders near the finish, none of them would help Millar reduce the deficit.

Almost everybody agrees that it was 'only natural' that the Spanish squads would be unwilling to work for a foreign rider in a foreign team. Some go as far as to describe it as a coalition, 'something you can see happen in any race'. Perhaps, but this coalition brought about the downfall of a rider who had a race sewn up, which only adds to the mystery aspect of it all.

that the Spanish squads would be unwilling to work for a foreign rider in a foreign team. Some go as far as to describe it as a coalition, 'something you can see happen in any race'. Perhaps, but this coalition brought about the downfall of a rider who had a race sewn up, which only adds to the mystery aspect of it all.

Some local riders and foreign journalistss point out that there had been a concerted campaign in the Spanish media during the previous week to the effect that Millar, converted into the symbol of all things foreign thanks to his 'unconventional' appearance, should not win the race. ("The Spanish public hadn't seen anyone with an earring before, so it was a great new thing to them. They hadn't long been out of the Franco era so probably some of them harked back to the good old days. I was more famous for having an earring than for being a bike rider, in fact they still relate to that today".) The Frenchman Eric Caritoux had won the event the year before by just six seconds from the Spaniard Alberto Fernandez, who had died that winter in a car crash.

Add to this fact tat Spanish cycling desperately needed to have a local hero and that the Vuelta needed to reassert itself within Spanish sport and the sponsors' DYC distillery is close to Delgado's home town of Segovia and it is easy to see how things did not pan out i Millar's favour. As Ruiz Cabestany points out: "When Berland tried to startmaking deals 20 kilometres fro the finish, everything had been agreed upon. And you don't go back on deals."

Kelme's directeur sportif in the race, Rafael Carrasco, has a more tactful explanation: "I wanted Recio to take the stage, and if we could help a Spanish rider win the Vuelta, well, so nuch the better. In terms of publicity for the team, it was just what we needed. The stage and the Spanish helping the Spanish. But it wasn' anything more than that. Txomin Perurena (Delgado's directeur sportif) didn't even turn up until we'd covered half the distance, which shows how improvised the whole thing was. Perico never even so much as took Recio out to supper to thank him."

Carrasco doesn't contradict Recio, who claims that "I could have won that day without any help and after some humming and hawing, my directeur sportif made me wait for Delgado. That year I was flying." However Recio paid a price for his stage win: the following day he withdrew from the race suffering from tendinitis. ("Rumour had it it that Recio didn't want to go to the medical control the following day. There hadn't been a test at Segovia that I knew about and I was suppoed to go there as I was race leader that morning.")

And what of the 'foreigners'? Millar admits now that he was ' naive and new to being leader in the race. It wasn;t like I was the patron in the Tour of Spain or anything like that. If i'd known then what I do now I would have reached some agreements." So surely it was down to Berland to do the talking? ("I was still learning so all this was new to me. Beralnd had seen the Peugeot riders being dropped when they went backwards on the first col, so he should have been known to do something then".)

Of the two foreign teams that seemed, as one journalist put it 'most propitious to doing deals', Kelly's Skil team was driving up the road ahead of Millar, and Panasonic, if they were apprached by a confused Beralnd at all, never seem to have got the message. ("According to Berland all the options were already taken by the time he realised the situation. There were no possibilities left well before the final hour".)

Two other factors seem to have helped Delgado as well; the terrain, which he knew like the back of his hand, and the fact that, in spite of the treacherous conditions – hail covered roads and a cold foggy day – he was one of the best descenders in the peloton at the time. 'He gained minutes virtually every time the road went downhill', affirms Van Looy.

However, perhaps things were not as clear cut as they may now seem. For a start Delgado claims that initially his breakaway partner did not want to work with him and that he dropped Recio 'by accident' on the Leones climb: 'I waited for him though', is Delgado's memory of how they did get together, In addition, Van Looy points out that Delgado was not at all pleased at first to find himself in the company of a faster man if it came down to a sprint for the stage at the finish. He adds: "Nobody sat down at the beginning of the stage and said, 'Right, today we do Millar.' It was a combination of mistakes made by his directeur sportif and unfavourable circumstances. Add to that the kind of coalition you can find any day in cycling, even though they don't normally have such a dramatic effect".

The final word should go to Millar: "The other pros can't make you win a race, but they can help you to lose one," the Scot once said, and nobody doubts that he, of all people, knows exactly how it feels to be 'helped to lose'. ("Exactly. Delgado didn't win. I lost. This was mainly thanks to circumstances which shouldn't have happened. I didn't begrudge Delgado at all because he wasn't to blame, but the other Spaniards didn't get gold stars in my notebook".)

Cycle Sport magazine February 1997.

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................palmares | a funny guy | a peiper's tale |the spanish years |

honour| the small yin | setting the record straight | millar on motorbikes | the book |

robert millar colnago c40 review | 1988 winning magazine interview | training | the outsider |

2008 interview | british road champion | the 2011 tour de France